Photos above: Maddie Ball

Article: Maddie Ball

One morning during the spring of 1994, just 13 years after moving onto her 27 acre property outside of Paola, Kansas, Lenora Larson was sitting on her porch with a neighbor when a butterfly glided by. It sparked her curiosity, and in her research she learned that it was a zebra swallowtail (Eurytides marcellus) and the reason for choosing her property as its home was the Pawpaw tree she had planted 12 years prior. The leaves on that tree happen to be the only food source for zebra swallowtails’ caterpillars.

“I had been so busy looking down at my plants that I never looked up. So, I started looking up and there were butterflies everywhere! This was because so many of the plants I had planted because they were cool plants were also butterfly hosts. I thought I need to start learning about this!”

It was this moment that sparked Lenora’s passion for insect conservation and the development of what is now a dynamic garden overflowing with nectar sources and host plants.

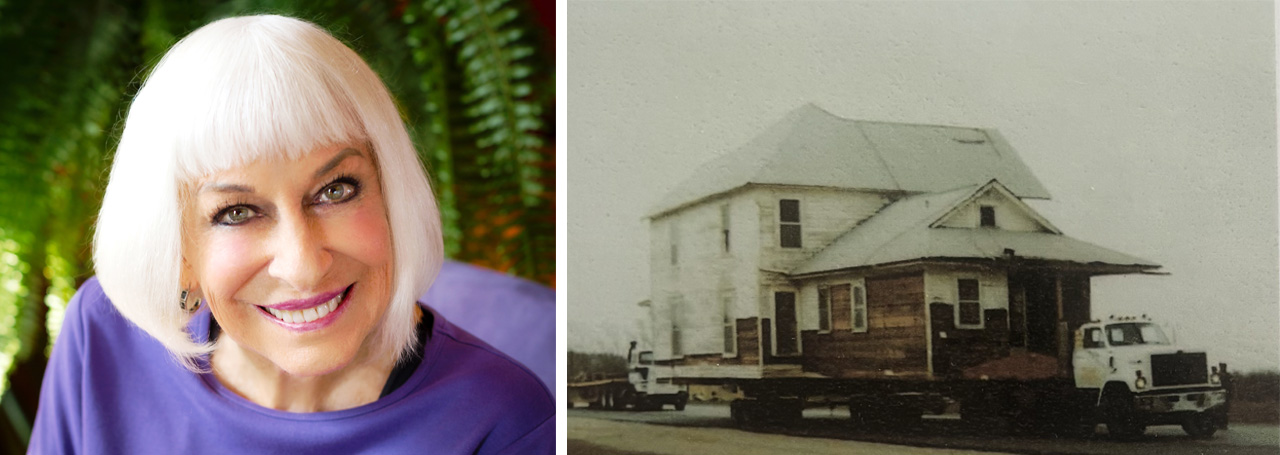

Photos: Lenora Larson. Pictured above, L-R: Lenora Larson; the 1890s farmhouse getting delivered down Highway 86 in March of 1981

After relocating from Detroit, Michigan to Kansas, Lenora and her husband had an 1890’s farmhouse delivered to the property they named Long Lips Farm after the Nubian Dairy Goats. The original goal was to raise goats but being the daughter of a certified landscape designer and a botanist, Lenora knew she wanted a garden as well. This was her first personal garden, and she quickly realized that there was a lot to learn. The management decisions she made early on (such as replacing the soil and spraying the pastures with 2-4D herbicide as the previous property owner had done) would later prove incongruous with the gardening mantra she came to embrace: Do as Mother Nature would.

“Mother Nature is my guide. Any problem, my first thought is that Mother Nature has been gardening for 250 million years; how does she deal with this? You will never see her dragging bags of fertilizer around a prairie or picking up all the leaves and putting them in a compost pile.” Lenora stopped spraying the pasture around 2007 and before long, a gray-headed coneflower appeared on its own, despite her belief that the damage of the harsh treatment was immutable. Her hope restored, she spent the next couple of years replacing the native prairie plants that had been killed by 75 years of biannual herbicide spraying.

“Originally the property was a tallgrass prairie as proven by the “weeds” that grew along the gravel county road. It was too degraded to be restored as a prairie, but certainly could be re-born again as a prairie ecosystem through re-planting and prescribed burns.”

Photos: Maddie Ball. Pictured: The Prairie Reimagined which Lenora shared is still recovering from a four year drought but maintains a wide variety of grassland plants including Tragopogon dubius (right)

The ‘Prairie Reimagined’ is now four acres of native grasses and plants including Yellow Salsify (Tragopogon dubius), Compass Flower (Silphium laciniatum), and Goat Weed (Silphium laciniatum) which Lenora shared is the host plant of the goatweed leafwing butterfly. She celebrates that most of the featured natives showed up in her prairie on their own including the Sawtooth Sunflower (Helianthus grosseserratus) and Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii). In the same vein of handing the reins to Mother Nature, Lenora welcomes plants that show up unexpectedly and is proud when her plants “take responsibility.” This ideology impacts her other two gardens as well: the prairie garden, full of mostly native host plants, and her butterfly garden, which is a hybrid garden full of ornamental flowers and natives.

Photos: Maddie Ball. Pictured above clockwise from left to right: One of many host plant labels made from rocks Lenora finds on the property; Lenora showing off two unexpected cycnia moth caterpillars found on a milkweed leaf in her ornamental garden; the native digger bee colony under Lenora’s porch, each nest hole dug by a female bee in the colony

Lenora walked me through these gardens for two hours, pointing out each plant and the part they play in supporting her recreated ecosystems. For example, the Hop Tree (Ptelea trifoliata) labeled as: CATFOOD” for the tiger swallowtail and the giant swallowtail. The giant swallowtail is the largest butterfly in North America and native to Kansas. Lenora cuts the trees in her butterfly garden to be shrub-size. Everybody wins with this gardening tactic; the nectar rich flowers continue to receive full sun, the swallowtail caterpillars can enjoy their preferred tender juvenile leaves, and Lenora doesn’t have to climb a ladder to see the caterpillars. Or the Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) that took her seven years to find during the age BG (Before Google). This plant hosts the spicebush swallowtail caterpillar and rarely self-seeds, which is a sign that the birds are enjoying the berries.

It wasn’t just the plants that had their moment in the spotlight during this tour. Lenora found and introduced me to two unexpected cycnia moth caterpillars (Cycnia inopinatus), adorable little orange caterpillars with gray eyebrows who, like the monarch caterpillar, can only eat Milkweed. She also had me peek at the native digger bee colony under her porch. “Thank goodness they chose me” Lenora remarked, and it’s true. Their survival is ensured not only by the absence of calls to an exterminator, but by Lenora’s care. Attuned with their life cycle, she arranges that during the season of reproduction they have both a nearby water source and a short commute to their favorite nectar source, Catmint (Nepeta faassenii), which she has intentionally planted near the colony.

Photos: Maddie Ball. Pictured above: Two different sections of the ornamental garden, both densely packed but intentionally planned based on color blocking and use of complementary tones such as purple and chartreuse.

The vibrant gardener is actively involved in the gardening community as an Extension Master Gardener, and a member of the Idalia Butterfly Society, Kansas Native Plant Society and a Monarch Watch supporter. Her property is certified by the North American Butterfly Association as a butterfly garden and by Xerces Society as a pollinator habitat. The combination of her career as a microbiologist and her training as an artist has produced a garden that is intentional both in aesthetics and in ecological purpose. As you might imagine, she has quite a bit of gardening wisdom and often, her phrasing is delightful.

“The best nutrient for any plant is last year’s dead body,” she shared when showcasing the resourceful mulch in her garden beds, consisting entirely of dead clippings and leaves she cut and returned to the soil.

While we were discussing the importance of doing your research, she explained that in her eyes, “Buying a plant is like getting married: You wouldn’t want to marry someone you know nothing about.” As a scientist, Lenora stresses the importance of learning. Take the time to know the plants you are putting in the ground, learn the habits of the species you are supporting, and observe Mother Nature at work!

“There is no substitute for the hard work of learning. No one is born knowing any of this, and you won’t have the passion unless you start to learn.”